Emma was not aware that Trassel, her dog, ate the last page of her (Swedish) passport. Not being aware of that detail, however, cost her denied entry into Serbia. The policeman in charge was acting “in accordance to the law” which ”did not allow him” to let her in on a ”non-valid document”. Rules are rules.

Emma didn’t check the state of her passport because she didn’t feel it’s so important. She didn’t feel it’s important because wherever she had travelled she didn’t really need her passport. Serbia is the furtherst that she ever went. The only border that she reached, the only place she needed the passport for so far.

Emma belongs to the European generation Y. They didn’t get the chance to memorize how Europe with borders looked like. They more or less started to travel when the bigger part of Europe became borderless.

The reality they encountered on their journeys is a Europe made up of different languages and levels of wealth, partly of different values, but in terms of space they met one relatively big entity. I mean, one can really travel for some time before hitting the first passport control.

Perceiving space in that way is quite comfortable. It’s nice to travel without thinking about visas, borders, controls, policemen. There is just one danger: it can turn into an illusion. People who don’t leave their ”security zones” easily start to believe that their protected borderless oasis is all there is in the universe. Then they are completely unable to conceive the notion of abroad.

My younger sister Nevena is a little bit older than Emma, but she is also a part of generation Y, just not the EU one. When the time had come for her to chose a university at which to study, Europe seemed to be the most apppropriate and promising choice. She applied, struggled for papers, got accepted and finally studied fine arts – in Utrecht, in Amsterdam, and in Granada.

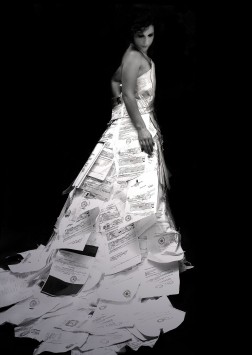

It definitely turned into a life experience. Her diploma work was ”Dress for Success”, a dress made of around 500 papers that she, as an alien, needed in order to finish her studies. (you can see it here and here). It’s more or less 10 years since she moved to Spain, but it’s still, as always, a paper, or two, that she is missing, to ”get in”.

I call that situation the one missing paper paradox. It’s just one paper defining whether you are in or out. Legal or illegal. Wanted or non-wanted. Where you can and can not go. Whether you can or can not work. It’s just one, but you never get it.

The agony lasts, and continues, and one shitty paper becomes your obsession, and starts to determine your life perspective. Questions like ”Why do I need that?”, ”How can I get that?” or ”Who is really in charge to define what is needed?” are elevated into metaphysical dimensions. Or just Kafkan.

Anna and I are one generation older than our sisters. We can say it’s Generation X, if that notion is applicable for Piteå and Belgrade. Up to a certain point we had very similar common ground – we grew up in egalitarian social states, and were raised within similar values, listened to similar music, watched similar films…

The experience gap appeared when we were of university age. On one side, the borderless Europe was being created, with one high Schengen wall around it. On the other side, lots of borders and big walls – from inside and outside – were being created in what used to be borderless Yugoslavia.

For Anna, the space had opened. She studied in France, Spain, Austria, and Ireland. She had the opportunity to travel and work all around the place, and she did. I got surrounded, from inside and outside. You had to be really good in high jump and pole vault to jump over so many high walls. To that borderless Europe I was not welcome with or without all the pages in the passport.

Getting the most ordinary EU visa meant so much humiliation, that I never even applied. For around 15 years, i.e. until I met Anna, I have not been travelling in that direction at all. Not even to visit my sister in the Netherlands and Spain. If I ever suffered from euro-centrism, during that time I definitely got cured from it. For good, I would say.

When I was staying in Brazil, travelling around, I learnt that to many South Americans ”European” is a synonym for ”colonial”. I was happy not to be labeled that way. Balkan was good enough for me. Outsider. Leftover of the leftover. That description fits relatively well how I felt. And how I still feel.

To Sweden I came with Anna. I knew that thanks to her and our relationship I should, supposedly, get the one missing paper. One day and maybe even sooner, as there is a saying in former Yugoslavia. Naturally, I expected some unpleasantness on the way to that day.

I was feeling kind of like Morgan Freeman in The Shawshank Redemption – when on a parole hearing, after serving 40 years of a life sentence, the young guy in charge asks him if he feels rehabilitated.

”Rehabilitated? Well, now, let me see. You know, I don’t have any idea what that means…I know what you think it means, sonny. To me, it’s just a made-up word. A politician’s word, so that young fellas like yourself can wear a suit and a tie and have a job. (…) So you go on and stamp your forms, sonny, and stop wasting my time. Because to tell you the truth, I don’t give a shit.”

My case was approved, same as Freeman’s. Miraculously, or not, I got that eternal one missing paper paradox solved painlessly. I have hardly seen the person in charge, we communicated mostly by e-mail. When I got the decision, it was hard for me to take it seriously. One day came too soon! My sister in Spain didn’t finish this in 10 years. She is tailoring another paper-dress now and I hardly have any papers for tailoring…

I instantly entered another film, you know Cinema Paradiso, that story about the boy Salvatore – Toto growing up in Sicily, whose mentor and best friend is Alfredo, a cinema operator in the local cinema. When Toto reaches maturity, Alfredo advises him to go into the world and not to allow nostalgia to drag him back… So, Toto comes back for the first time thirty years later, just after hearing Alfredo died, to attend the funeral.

”You must be tired. You can rest…” his mother tells him after the arrival. ”No, mamma, it only takes an hour by air, you know…”, Toto replies.

”You shouldn’t tell me that now. After all these years!”, mother concludes.

After all these years of living in the one missing paper paradox, of applying and waiting for visas, of interrogations and humiliations on borders, to get that one missing paper in ”an hour, by air” is surreal. What the endless hassle was all about?

One of the people I’ve met in Stockholm in that time was Martin, a guy involved with theatre and radio. We ended up talking about possible projects connected to ”Creative Force”, a project by which the Swedish Institute is supporting ”creative encounter” between Swedish and (cultural) organizations throughout the world. The dialogue had an unexpected twist.

”You know… Sweden is not really Europe… We are far away, geographically alienated from the continent… You down there, you are in the centre of it…”, Martin said.

”No, no, no…Come on… You are Europe! Officially. Down there, we are officially out…”, I replied.

We laughed. Everything is about perspective and points of reference.

Talking with Martin, I realized one thing: It is through Sweden, that is not Europe, that I entered to EU-rope. Officially. Some borders are closed, some walls are high, but gates of absurds and paradoxes are always wide open. In that sense, the world is really like from John Lennon’s imagination – “as one”. Who says that there is no hope?